Lies of P is a rare gem in the recently saturated Souls-like genre. In fact, it may be the first great 3D game to adhere to that genre’s formula not made by From Software.

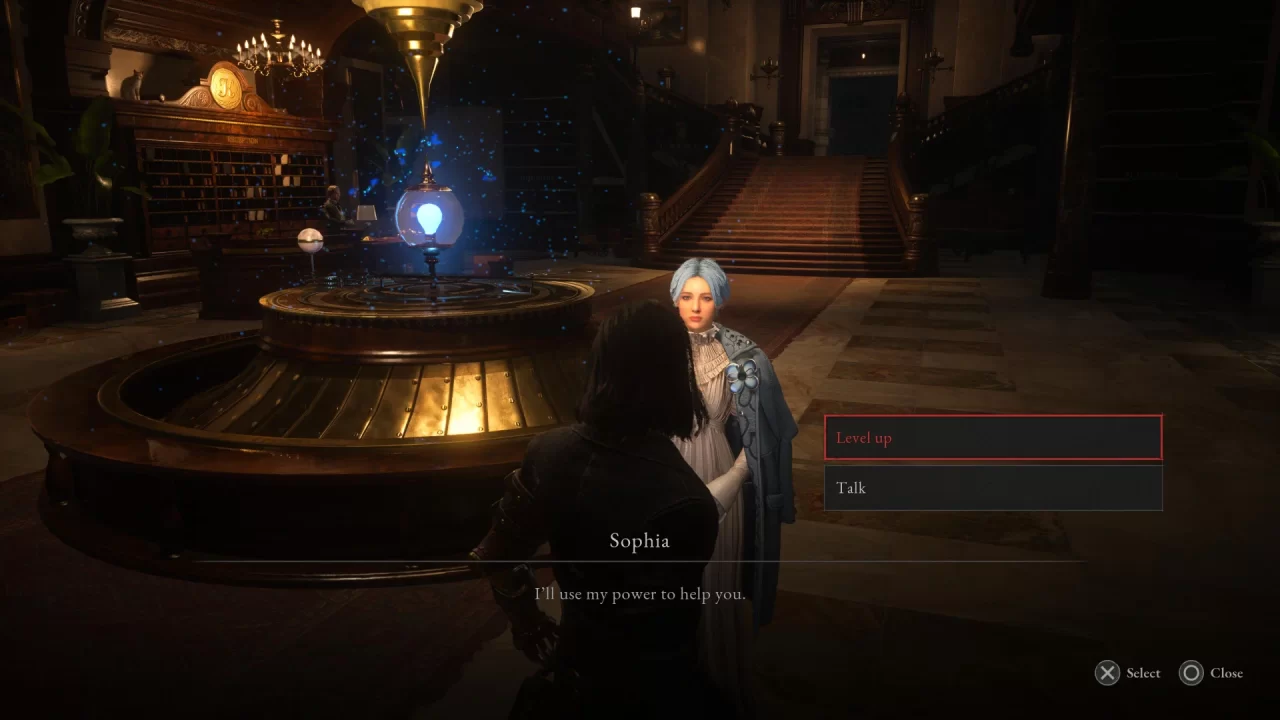

Developers Neowiz and Round8 treat the Souls blueprint like a religion for Lies of P. Nearly all the sacred pillars of From’s design are here: gathering universal currency by killing enemies, backtracking to that currency when you die, circling through levels with unlockable shortcuts, “bonfires,” and an item that will teleport you back to them (which you thankfully get very early in Lies of P), learning boss patterns in order to defeat them, stories told through cryptic dialogue and item descriptions, a tranquil central hub, uncanny romance stories, a softspoken immortal leveling maiden, and, of course, a poison swamp or two for good measure. There is clear care taken in preserving the legacy of this beloved genre, with Neowiz even advertising the game as a “Souls-like” online, something other dabblers in the genre like Respawn, Hexworks, Team Ninja, and Housemarque notably do not do; though, to be fair, these all put more substantial twists on the genre than Lies of P does.

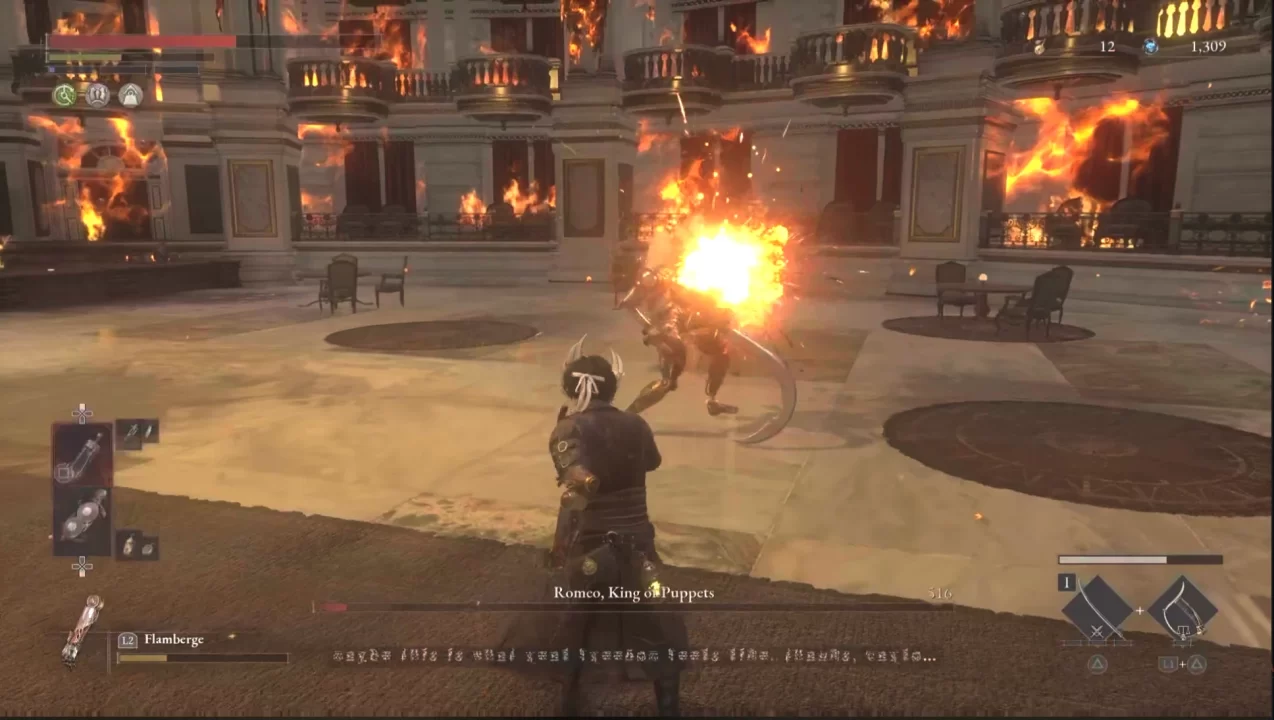

This religious adherence to the Souls Testament goes a long way in making Lies of P‘s gameplay loop compelling. The game’s “zones” are very rewarding, with plenty of loot and fun side stories to seek out, varying enemies and minibosses to fight, and lots of helpful and familiar circular shortcuts to unlock. The zones are so well-connected that a “no bonfire” run is highly achievable, something fans of the genre may be happy to hear. Boss battles are tough, but (at least the early fights) can be won with persistence and observation — the adrenaline rush of beating some of the bosses in Lies of P may even be a step above that of From Software’s boss battles. Also, the characters you meet along the way are compelling, interesting, and universally strange or cryptic. It is very clear that Neowiz and Round8 worship certain aspects of this genre, especially ones that will wet the whistle of the genre’s “hardcore” fanbase.

Though, perhaps like other religions, drawbacks of this devotion exist, especially when the game’s developers misappropriate some of the key commandments in the Souls bible. Firstly, the game has no multiplayer. In any other genre, this is a moot point, but the origin of this genre demands it. Demon’s Souls was actually not built to twist conventions on difficulty in videogames. The difficulty twist was a product of cooperation-focused design that Hidetaka Miyazaki originally came up with after his car got stuck in heavy snowfall along with the cars around him, and through cooperative pushing, they all got free and drove home. “Mutual assistance between transient people” is his vision for Souls design. Cooperation — through summons, but also in-game comments and out-of-game wikis and social interaction — actually makes the games accessible and fun to a much wider audience than the “hardcore” isolated devotees the series famously attracts. Those wishing to spend their time on something other than rote memorization and arbitrary skill checks may not enjoy Lies of P because of its lack of multiplayer, especially when they reach the last few boss fights. It is unfortunate that instead of taking a traditional focus on cooperation, Lies of P focuses its gameplay on something much duller: test-taking.

Another key gameplay misappropriation is that Lies of P‘s levels/zones do not adequately prepare players for boss fights. You can play each zone the exact same way: bowl over enemies by keeping your distance and attacking carefully or creatively use items to get by. However, bosses will require you to play aggressively, time blocks rhythmically (though the rhythm, unlike in games like Sekiro and Nioh, is all over the place here), and manage your loadout appropriately. I found that grinding for experience helped me very little for boss fights, so it wasn’t even worth it to revisit zones in preparation — not that any of the zones provide much Ergo, the game’s version of souls/blood echoes/runes. You also can’t adjust your loadout until very late in the game, notably after the first major skill check boss (one not unlike Smough and Ornstein). This is a crucial feature, by the way, especially if you do not spend your Ergo wisely on leveling one core skill early on. Also, that skill better be Technique or Advance, because Motivity-scaling weapons are poopoo in comparison.

It is clear to me that Lies of P forgot a few of the lessons of its ancestors. It desperately needs multiplayer to curb its wily difficulty, and it needs to mind the quality of life upgrades across the years in the Souls titles. Lies of P could majorly benefit from more balanced early-game weapon options, weapons that don’t “tink” against walls (one of my favorite changes from the Dark Souls 2 era), and a better-thought-out “magic” system — hint: pricey consumables ain’t it.

Of course, the other ways Lies of P diverges from its established formula are smash hits, in my opinion. First, Lies of P tells a more rigid and clear story than its kin, mainly through interspersed cutscenes and re-readable dialogue from hubworld characters. This sets the stage for its more cryptic side stories, and it doesn’t alienate those who are here for a legible main story or perhaps just Pinocchio vibes.

Speaking of which, Lies of P‘s twist on the old fable is an extremely compelling one. It is certainly loyal to the material established by Collodi, with allusions to familiar characters like the Fox and Cat, Romeo, and the Blue Fairy, as well as a similar darkness — though I might say Lies of P is not quite as dark as Adventures, a book which originally ended on Pinocchio being robbed and hanged to death by Fox and a grotesquely dismembered Cat. But it is also a wonderful modernization of not only the pre-Communist Manifesto that is Adventures of Pinocchio with its similar tale of an exploited working class, but also the thetical Disney film which has overtaken the social perception of the character.

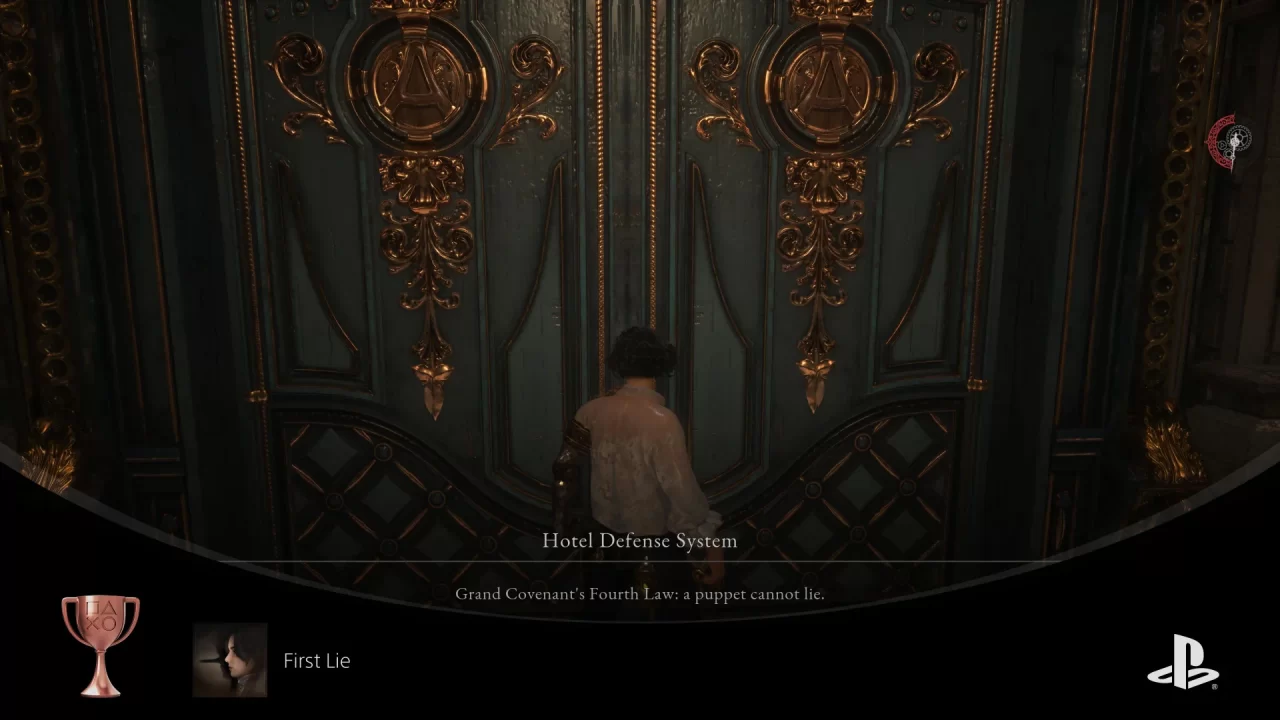

It flips the idea that lies are a hard moral line one should not cross, something only teased in the novel (Pinocchio’s nose only grows when he lies selfishly in the book, and not as a rule) but that the Disney film ran with. In Lies of P, lying is almost exclusively used to spare people from heartbreak or undue strife, or as an apprehensive necessity (see image below); plus, it has gameplay benefits that I won’t spoil here but are rad. The familiar human labor of lying for the sake of others feels like a logical evolution of Collodi’s original ideas, and it certainly feels like a necessary dismantling of the oversimplified moralizing of the 1940 film. Furthermore, capitalism is, in a way, what makes Pinocchio a boy: in Adventures, Pinocchio only became a boy because of the pressures from consumers for Collodi to reevaluate the ending; in the movie, his boyhood is the answer to unwritten post-Code rules of consumer-friendly conduct. I love that the game reconciles with this discomfort in only offering boyhood through tough moral decisions, some of which trouble its capitalistic origins.

In terms of gameplay, Lies of P diverges from its inspiration in a few welcome ways. First, it introduces weapon handles, which have fun additional lore text and serve as scaling devices and magic-imbuers. You can combine these weapon handles with any of the blades of another weapon, making for some powerful combinations. Admittedly, you’re better off mainlining one of the game’s boss weapons, but it’s still fun to attach a spinning electric chainsaw to a dagger handle and wreak havoc. Lies of P also introduces a robotic prosthetic attached to the left trigger button that can grapple, burn, electrocute, and even set destructive mines on the ground. This, combined with weapon-handle combos and “Quartz” upgrades (similar to a skill tree), makes for rich and varied approaches to combat. Also, you can partake in “Fashion Souls” here without affecting your loadout, as cosmetics offer no protection, which is a super welcome change.

Lies of P‘s twist on the Belle Epoque era is also among its highlights. The level designers and artists worked their butts off making this game beautiful and evocative of that aesthetic. The foggy, somber tone of the Disney movie is at play, but so is the architectural fantasy of 1800s France, and it is all wrapped in a Bloodborne-y steampunky wrapping paper. In short, the game is gorgeous. It is a symphony for the eyes, dark and colorful and foggy and vivid all at once. Visiting new areas in the game always brought me joy simply by my desire to explore the game’s compelling spaces.

The soundtrack is also a highlight. From epic orchestrals to quiet ambiance to poppy records you can play in the hub world, the game’s tracks never cease to amaze me. The records you find hidden across the game are some of my favorite songs in all of music this year, and the endgame boss tracks were mind-blowing. Needless to say, the audiovisual experience of playing this game is miraculous, exceeding my expectations to the point where I think Lies of P might be a better looking and sounding game than anything the genre has produced, even director Choi Ji-Won’s favorite series in the genre, The Legend of Zelda.

Choi Ji-Won’s quirky answer aside, it is clear that he gets what he is making, and this is especially true when it comes to performance. Other than those pesky wall tinks, Lies of P plays like butter, even in areas that would have no doubt chugged along in previous titles, such as the final boss area. The game works with complex particle effects, huge areas with very little pop-in, and lots of moving objects simultaneously, and it seemingly doesn’t break a sweat. I can’t speak to Ji-Won’s claim of great Steam Deck performance, but on PS5 it plays tremendously well.

As apprehensive as I am about the game’s spikey difficulty and its misrepresentation of the Souls formula, I mostly had a great time playing Lies of P. I don’t think casual genre fans will vibe with this because it is a bit “hardcore.” But, if you enjoy rote memorization or other antiquated structures of examination, and you can see past some quality-of-life mishaps, by all means, give Lies of P a whirl because it’s well worth your while. I’m not even trying to be cynical here; I actually think this game offers a familiar, perhaps even comforting, challenge to those who have adjusted to this model of learning and doing. Of course, I fundamentally disagree with it, but that’s just, like, my opinion.

Lies of P certainly evokes the likenesses of the game we all know it is trying to emulate — that’s right, Nightmare Creatures 2 (j/k, it’s Dark Souls). However, it is polarizing to me; it marks a step backward in several ways from the design of its inspiration. However, it also offers a few alternative modes of stepping forward from those designs, such as robust weapon adjustments, streamlined cosmetic options, and a fun new skill tree in Quartz upgrades. It also offers a more obvious central story, one that does a good job of recognizing its ancestry while gracefully appropriating it for the present cultural moment. It is just a bummer that, from a gameplay standpoint, Lies of P fails to remember where it came from. I wish Ji-Won had stuck by his guns when he claimed that he wanted to make “a game [that starts] from the joy of the user, and not from the benefit that they would make from the game.” Still, I am eager to see what his team makes next. I’m sure it will be well-crafted and beautiful. I just hope it doesn’t merely puppet its genre next time, but instead embraces all of its pieces to make the experience feel more familiar, because after all there’s no place like home.