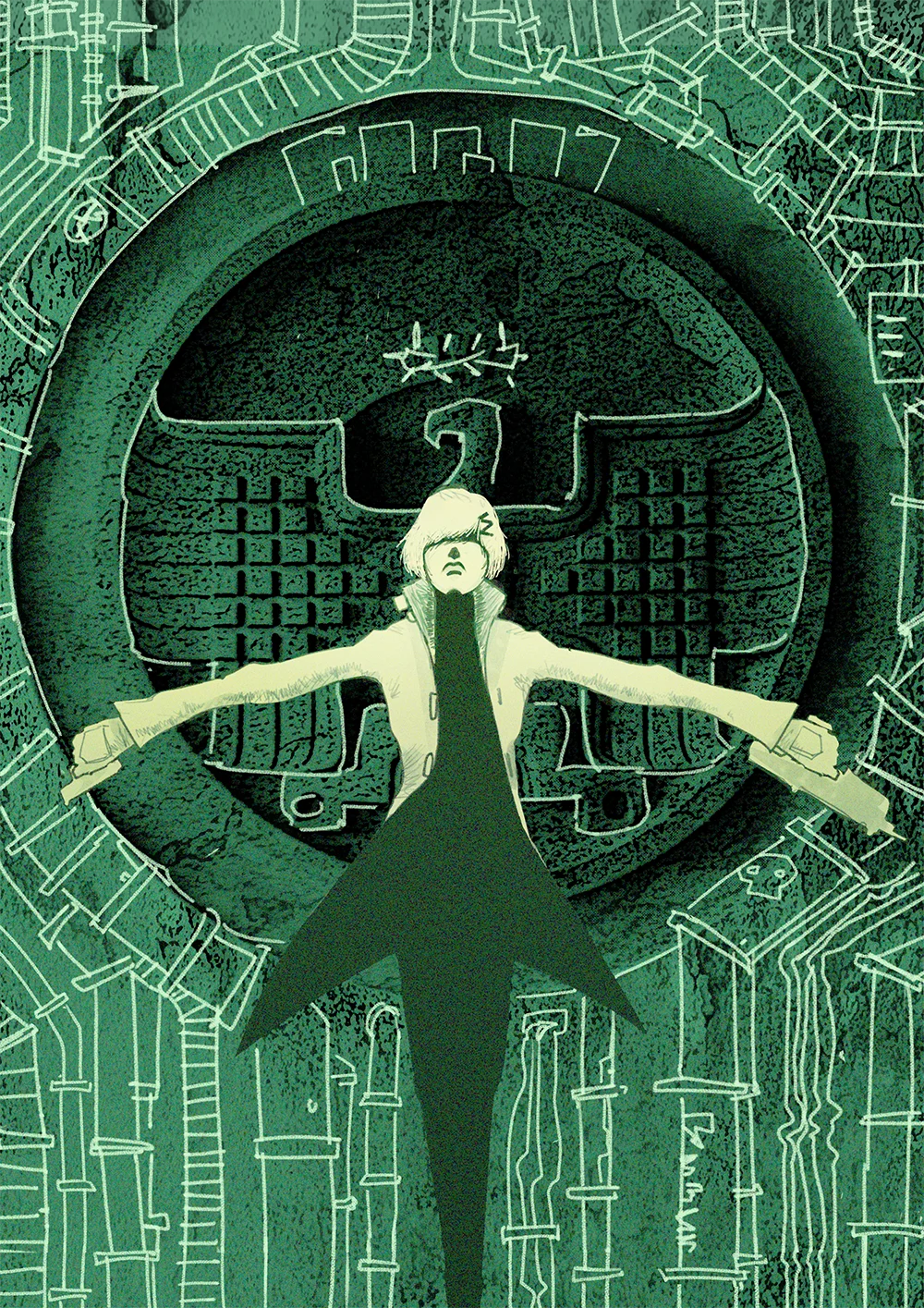

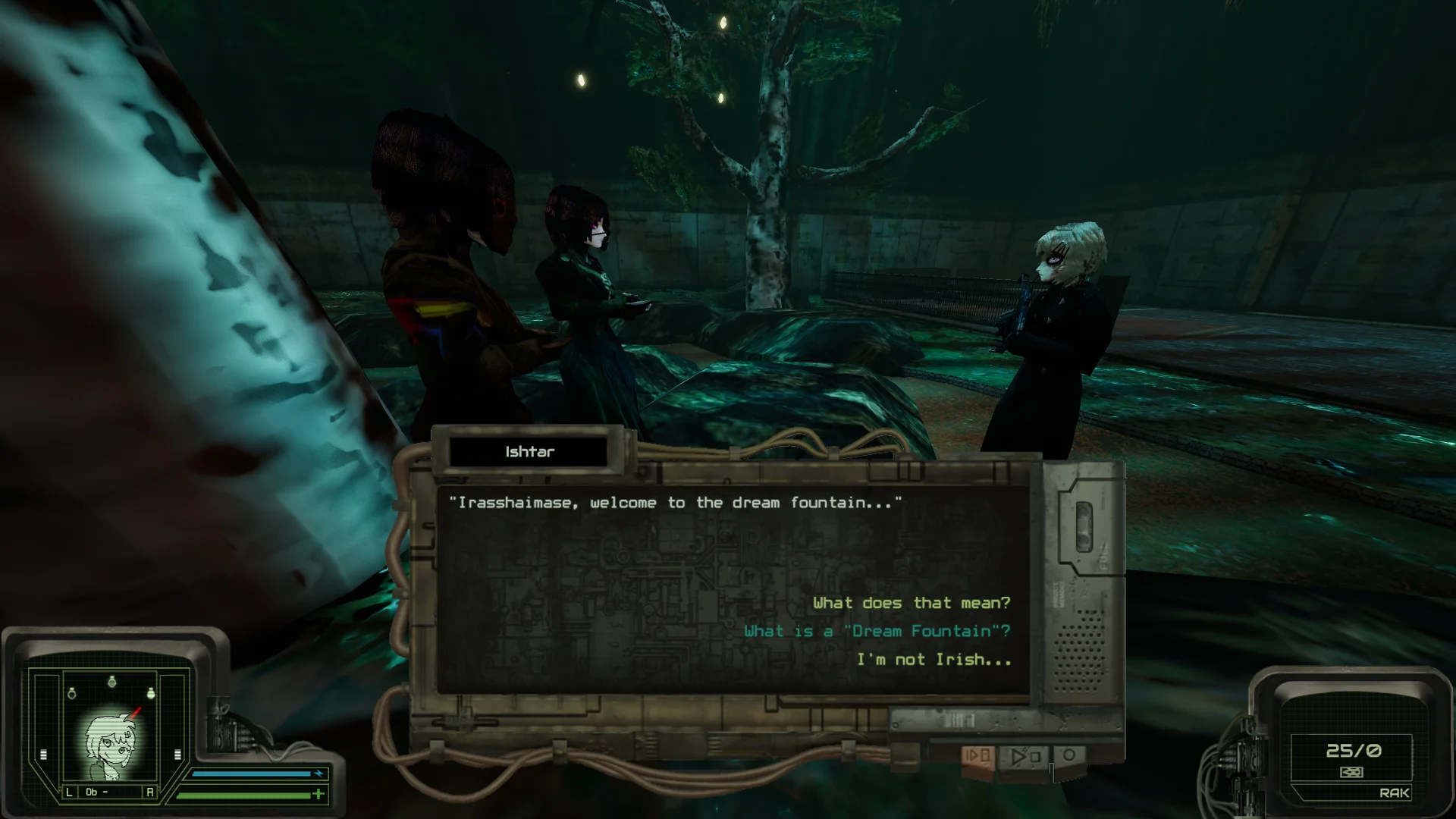

A cyberpunk stealth game set in an alt-history Poland, Peripeteia is the debut title from developers Ninth Exodus. It’s inspired by games from Ion Storm (Deus Ex) and Looking Glass Studios (System Shock). It launches into Steam Early Access on February 21st, 2025.

Peripeteia